Southern Vermont faces a challenge. A network of dams, some dating back 250 years, play a major role in controlling the flow of water down the mountains into the Connecticut River and finally to the Long Island Sound. What dams are really necessary? Would we be better off with or without them?

During the first five weeks of school these questions and tradeoffs were explored by 7th and 8th grade students of the Flood Brook School. While their ultimate decisions are worth noting, the real value comes in the process undertaken in reaching a conclusion.

“This project is all about taking the fundamental skills learned in class and applying them to a real world question,” said FBS Social Studies teacher Cliff DesMarais. “Call it transferable skills or critical thinking, the end result is taking what you’ve learned and showing what you can do.”

The real world question facing the middle schoolers was how best to manage the local watershed in Southern Vermont. Recent flooding in the mountain towns gave the project a sense of urgency and relevance.

“The watershed project was a pretty powerful learning experience for our students,” said FBS Principal Johanna Liskowsky-Doak. “The connection to their own life experience of the floods shows the value of using real world applications to content material.”

To explore the question, the students visited four dams, some dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries, to see first hand the impact of blocking a river to create power, fashion a reservoir, and control the flow of water.

In conducting their research the students rolled up their sleeves and pant legs and waded into the water. They took scientific measurements above and below the barriers to quantify differences in temperature, PH levels, oxygen, turbidity, and levels of sediment. They explored variations in life forms with a focus on the presence of invertebrates, a sign of a healthy ecosystem.

“I really liked getting out into the field and conducting research,” said one student. “The project made me feel like I was doing something for my community. That was important to me.”

The trips also provided an introduction to lifestyles from an earlier time. The trip to the Weston Dam, for example, included a tour of the Old Mill Museum and the nearby Farrar-Mansur House. Inside the dwelling students got a taste of growing up over 200 years ago.

“I can’t imagine being one of 13 children!” said one student. “It was kind of unfair because the boys got to go to school and the girls stayed home to sew,” said another.

Communities in the 18th century clustered near rivers as a source of power and a reliable source of water needed for food. The students marveled at the ingenuity of the early settlers who developed a grinding process using mill stones to turn grain into flour that still functions today. .

The student itinerary also included stops at more recent structures, such as the Townshend Dam built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The barrier constructed in 1961 has prevented millions of dollars in flood damage downstream while also creating recreational opportunities for boating and fishing, as well as generating renewable energy from its hydroelectric plant. Another 20 century dam at Bellows Falls attracted the students' attention with its fish ladder designed to help them navigate upstream to spawn.

The gathering of information allowed the students to explore the trade-offs to consider in deciding the fate of the local dams. When operating as intended, the barriers control the flow of water and minimize flood damage saving millions of dollars. There are also the collateral benefits of added recreational usage on and around the reservoir and renewable energy.

On the other hand, the student research confirmed that over time the body of water behind the dam is warmer, with more turbidity, lower PH levels, and less oxygen making it less healthy for fish and other life forms. Then there is the issue that as the water is more stationary behind the dam sediment builds up and minimizes the ability to prevent flooding downstream, sometimes making if more dangerous than what it would be without the dam.

From the readings taken downstream from the dams, the students confirmed that more free-flowing river system would result in a more healthy, natural habitat for living species. But if the dams were removed would the flood damage worsen?

To supplement their research in the field, Flood Brook brought in guest speakers to provide expert insight into the process. Kathy Urffer of the Connecticut River Conservatory, for example, made the case for rethinking the future with an emphasis on protecting the environment. A Town Selectman spoke to the students about the importance of weighing the cost and benefits of removing the dams or taking periodic steps, like removing sediment, to extend their useful life.

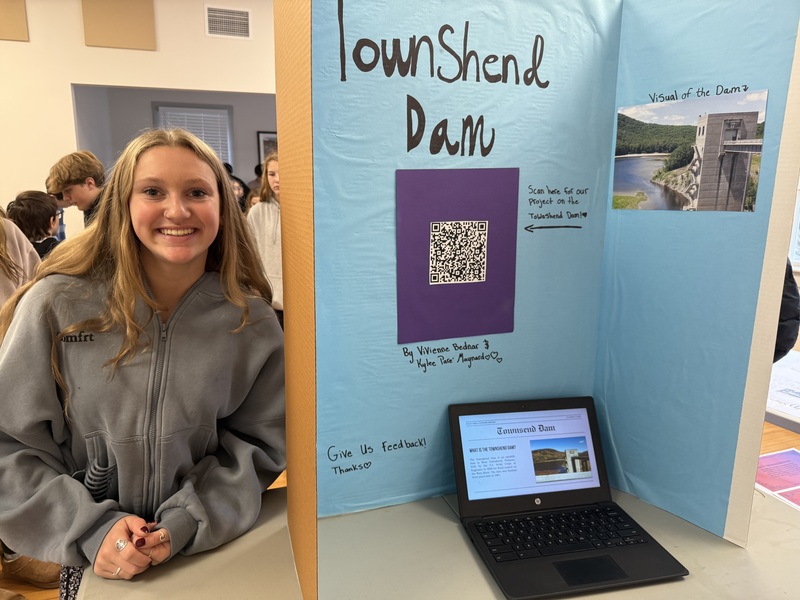

At the end of the project the students broke into teams to complete their analysis and make recommendations supported by facts. They then used their communications skills to design presentations that were put on display at the Londonderry Town Office. The results were delivered on posters, iPads, scale models, brochures, booklets and more.

“The most exciting for me as a teacher was to see how interested the kids were in the river and how reflective they were of learning on-site versus in a classroom,” said FBS science instructor Erica Bizaoui. “The process allowed them space to experience the impact of the dam and reassess their original ideas. Many students changed their mind based on facts and that’s what is called learning.”

(Photo above: Students at the Williams Dam see first hand how sediment builds up behind the barrier and minimizes the ability to prevent flooding downstream.)

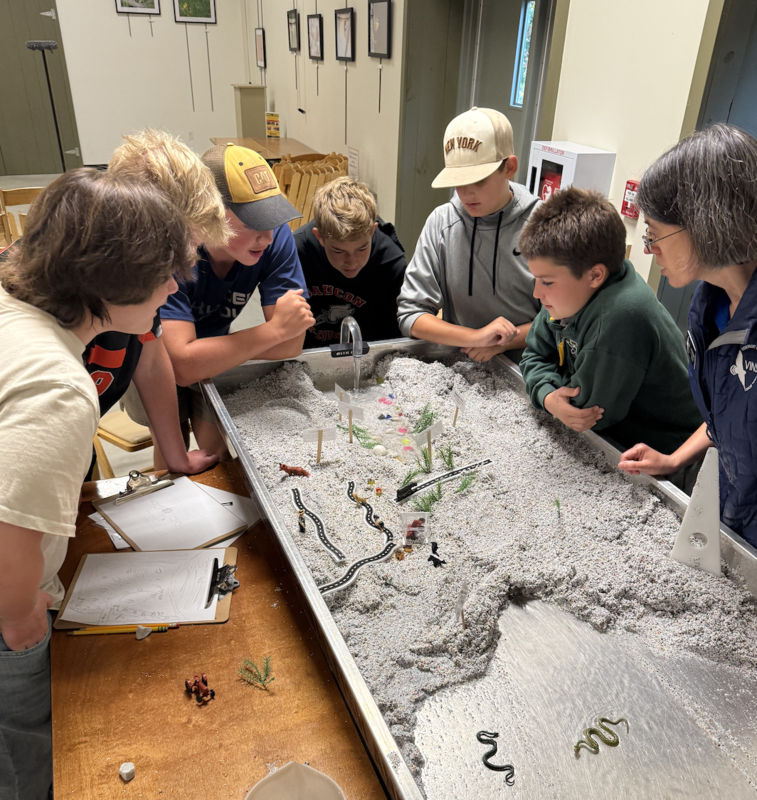

At the Vermont Institute of Natural Science the students interact with the stream table to learn about stream morphology, erosion, and flood control.

These students discovered a macro invertebrate during their trip to the Flood Brook stream where they were introduced to the testing protocols to be used during their project.

The young Flood Brook researches are briefed by the Army Corps of Engineers inside the gatehouse at the Townshend Dam.

At the Old Mill next to the Weston Dam students learn how water power turns stones to grind grain into flour.

In conducting their research the students waded into the water and took scientific measurements of water temperature, PH levels, oxygen, turbidity, and levels of sediment.

In November Flood Brook students presented their findings in an exhibit that was featured at the Londonderry Town Office.